The devastating wildfires currently ravaging Manitoba have cast a harsh spotlight on the disproportionate impact these disasters have on First Nations communities, revealing troubling patterns of environmental injustice that demand immediate attention. As flames continue to consume vast tracts of northern Manitoba’s boreal forest, Indigenous communities are facing not only immediate evacuation challenges but also long-term threats to their traditional ways of life.

“This isn’t just about losing homes—it’s about losing cultural heritage and traditional lands that have sustained our people for generations,” says Chief Stanley Barkman of Chemawawin Cree Nation, where over 300 residents have been forced to evacuate. “Every acre burned represents a piece of our identity that cannot be rebuilt with mere lumber and nails.“

The current crisis underscores a disturbing reality: First Nations communities face 18 times more evacuation events than non-Indigenous populations, according to recent data from Indigenous Services Canada. This stark disparity reflects broader patterns of environmental inequality that have persisted for decades across Canada.

Environmental justice advocates point to systemic issues underlying this disparity. “Indigenous communities are often located in remote areas with limited infrastructure and emergency response resources,” explains Dr. Melissa Thompson, environmental policy researcher at the University of Manitoba. “When combined with the accelerating impacts of climate change, this creates a perfect storm of vulnerability.”

The economic toll compounds the cultural devastation. Many evacuated residents have lost not only their homes but also their livelihoods. Traditional hunting grounds, medicinal plant gathering areas, and trap lines that provide both sustenance and income have been destroyed in the infernos, creating economic hardships that will persist long after the flames are extinguished.

“We’re talking about communities where traditional land-based activities remain essential components of both cultural identity and economic survival,” notes Thompson. “These aren’t simply recreational activities—they’re fundamental to well-being and self-determination.“

The provincial and federal responses have been criticized as insufficient by many Indigenous leaders. While evacuation efforts have successfully moved people to safety, the longer-term recovery planning lacks appropriate cultural sensitivity and community-led approaches. The politics of disaster response has become increasingly contentious as climate change intensifies these events.

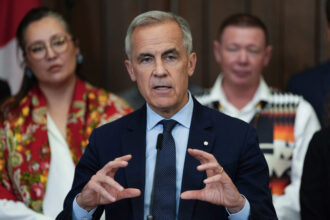

Chief Peter Redhead of Shamattawa First Nation has been particularly vocal about the need for Indigenous-led emergency management systems. “Our people have intimate knowledge of the land and traditional ecological wisdom that should be central to both prevention and response strategies,” he stated at a recent press conference. “Yet we continue to be treated as victims rather than partners in these efforts.”

The current crisis in Manitoba mirrors similar patterns seen across world Indigenous communities, where climate change impacts hit hardest among those least responsible for causing the problem. This has prompted growing calls for climate justice frameworks that acknowledge historical inequities while building resilience for the future.

“What we’re witnessing isn’t simply a natural disaster—it’s the manifestation of colonial policies that have systematically placed Indigenous communities in vulnerable positions while simultaneously undermining their capacity for self-determined responses,” argues Indigenous rights advocate Sarah McIvor.

As Manitoba’s wildfire season continues, with forecasts suggesting conditions may worsen before improving, the immediate focus remains on safety and basic needs. However, the conversation is already shifting toward longer-term questions about reconstruction, environmental protection, and governance structures that can better address these recurring challenges.

The business of rebuilding will require significant investment, with preliminary estimates suggesting costs could exceed $100 million. But Indigenous leaders emphasize that true recovery means more than replacing physical infrastructure—it requires addressing the underlying systems that create such disparate impacts in the first place.

As we witness these communities facing yet another environmental crisis, a critical question emerges for all Canadians: Will this disaster finally prompt the meaningful structural changes needed to address environmental injustice, or will it become yet another chapter in a continuing story of inequitable impacts and inadequate responses?