The critical shortage of forensic psychiatric beds in British Columbia has reached alarming levels, with mental health advocates and legal experts warning of a system at its breaking point. Patients deemed unfit to stand trial or found not criminally responsible due to mental disorders are facing unprecedented wait times, sometimes remaining in jail cells rather than receiving the specialized care they urgently need.

“We’re witnessing a humanitarian crisis unfolding within our justice system,” says Dr. Eleanor Walsh, clinical director at the Vancouver Mental Health Coalition. “Individuals experiencing severe psychiatric episodes are being warehoused in correctional facilities that lack the therapeutic environment and specialized treatment these vulnerable people require.”

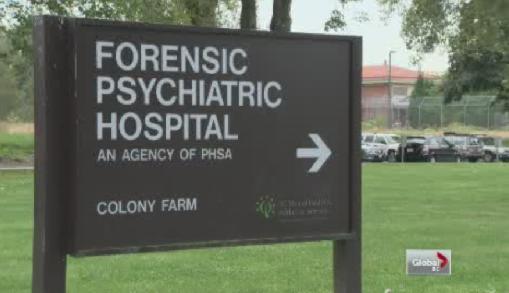

The province currently operates just one dedicated forensic psychiatric hospital in Coquitlam, which has been operating beyond capacity for years. According to internal documents obtained through freedom of information requests, the 190-bed facility has maintained an occupancy rate exceeding 97% since 2019, with patient overflow regularly diverted to already strained regional hospitals.

Provincial court judges have begun voicing frustration from the bench about the lack of available beds. Last month, Justice Margaret Wilson publicly criticized the system after a defendant with schizophrenia spent 67 days in pre-trial detention despite a court order for psychiatric assessment, calling it “a profound failure of our mental health infrastructure.”

The British Columbia Civil Liberties Association has documented a 38% increase in cases where individuals with severe mental illness are held in jails rather than treatment facilities over the past three years. Their recent report highlights that these delays not only violate constitutional rights but often exacerbate psychiatric conditions, creating a destructive cycle that becomes increasingly difficult to break.

Health Minister Adrian Dix acknowledged the challenges during a press conference last week, stating: “We recognize the pressing need for expanded forensic psychiatric services and are actively developing a comprehensive plan to address these shortfalls.” However, concrete timelines and funding commitments remain undefined.

Criminal defense attorney James Chen, who specializes in cases involving mental health issues, describes the current situation as untenable. “Every week, I meet clients who are deteriorating in jail cells when they should be receiving treatment. The system is failing those who are most vulnerable and least able to advocate for themselves.”

Medical professionals point to several factors driving the bed shortage crisis, including increased case complexity, staffing challenges, and insufficient community-based supports that could prevent hospitalizations. Dr. Raymond Chow, forensic psychiatrist and consultant to the provincial health authority, emphasizes that “modern forensic psychiatry requires a continuum of care options—from high-security inpatient units to step-down facilities and robust community treatment teams.”

Indigenous advocacy groups have raised additional concerns about cultural barriers facing First Nations clients within the forensic system. “Our people are disproportionately represented in these statistics, yet face significant obstacles in accessing culturally appropriate mental health services,” notes Samantha Williams of the First Nations Health Council.

Several families of patients caught in the system have begun speaking out. Elizabeth Donovan, whose son has waited nine weeks for transfer to the forensic hospital, describes the ordeal as “watching someone you love suffer needlessly because the infrastructure simply isn’t there to help them.”

The provincial government has committed to exploring several potential solutions, including expanding the existing Coquitlam facility, developing regional specialized units, and strengthening diversion programs that could reduce system pressure. Mental health advocates, however, remain skeptical about the timeline for implementation.

As pressure mounts from all quarters, the fundamental question remains: can British Columbia overcome decades of underinvestment in forensic mental health services quickly enough to prevent further harm to those caught between criminal justice and psychiatric care? For hundreds of vulnerable British Columbians and their families, the answer cannot come soon enough.