The quiet lakeside community of Kingston, Ontario has been thrust into crisis mode as public health officials confirm a deadly outbreak of Legionnaires’ disease that has already claimed one life and left several others hospitalized. The bacterial infection, which typically spreads through contaminated water systems, has sparked urgent investigation efforts across the eastern Ontario city.

“We’re facing a concerning cluster of cases that demands immediate attention,” said Dr. Helena Jaczek, Kingston’s Chief Medical Officer, in an emergency press briefing yesterday. “Our teams are working around the clock to identify the source and prevent further infections.”

According to Kingston Public Health, at least 12 confirmed cases have been identified since early June, with the fatality reported late last week. The victim, whose identity remains private due to family wishes, was reportedly an elderly resident with pre-existing health conditions that increased vulnerability to the disease’s severe pneumonia-like symptoms.

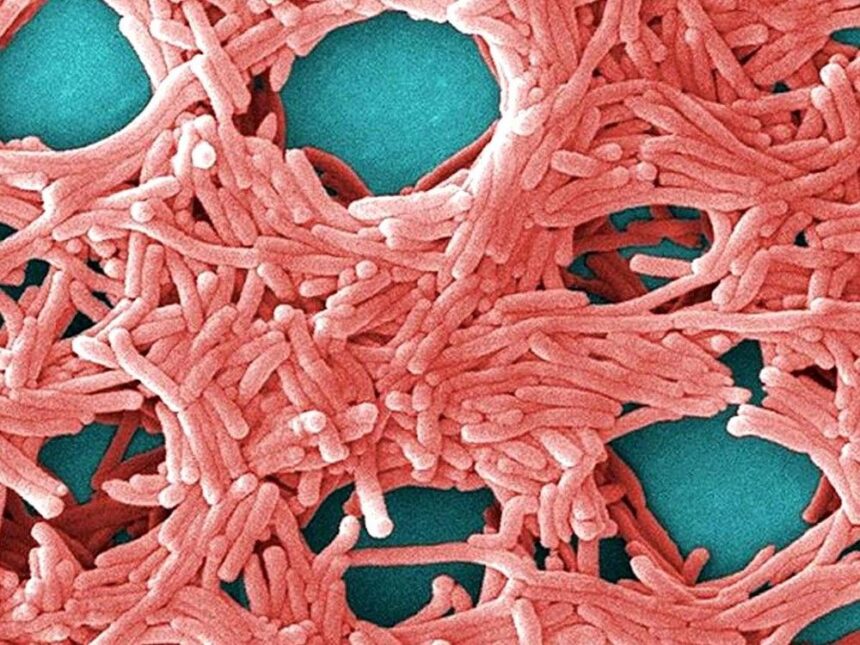

Legionnaires’ disease, caused by Legionella bacteria, is not transmitted person-to-person but spreads when people inhale contaminated water droplets. Common sources include cooling towers, hot tubs, decorative fountains, and complex plumbing systems—particularly in larger buildings or facilities where water may stagnate.

Provincial health authorities have deployed specialized environmental testing teams to sample water from multiple sites across Kingston, focusing on several downtown hotels, a community recreation center, and two healthcare facilities. Early investigations suggest the outbreak might be linked to a recently renovated cooling system in the city’s commercial district, though officials caution that conclusive evidence remains pending.

“Testing of this nature is methodical and takes time,” explained Dr. Kieran Moore, Ontario’s Provincial Health Director. “What’s crucial now is that vulnerable populations—especially older adults, smokers, and those with compromised immune systems—remain vigilant about symptoms including high fever, cough, muscle pain, and headaches.”

The Ontario Ministry of Health has issued a provincial alert to healthcare providers, requesting enhanced surveillance and immediate reporting of suspected cases. This outbreak represents the largest Legionnaires’ cluster in the province since 2019, when seven cases were linked to a cooling tower at a Hamilton shopping center.

Local businesses, particularly in the hospitality sector, report growing concerns about potential economic impacts. “We’re implementing all recommended preventive measures and additional water testing,” said Simone Laurent, president of the Kingston Hotel Association. “But there’s understandable worry about visitor confidence during our peak tourism season.”

Public health officials emphasize that municipal drinking water systems remain safe, as the city’s water treatment protocols effectively eliminate Legionella bacteria. The risk primarily involves specific building systems where conditions allow bacterial growth.

For vulnerable residents, health authorities recommend straightforward precautions: avoid high-risk settings with visible water mist, ensure home hot water heaters maintain temperatures above 60°C (140°F), and seek immediate medical attention if experiencing respiratory symptoms, particularly following stays in public accommodations.

As emergency response teams continue their investigation, this outbreak raises critical questions about aging infrastructure maintenance and public health preparedness across Canada’s mid-sized cities. How will municipalities balance essential infrastructure upgrades against limited budgets while protecting public health from preventable bacterial threats?