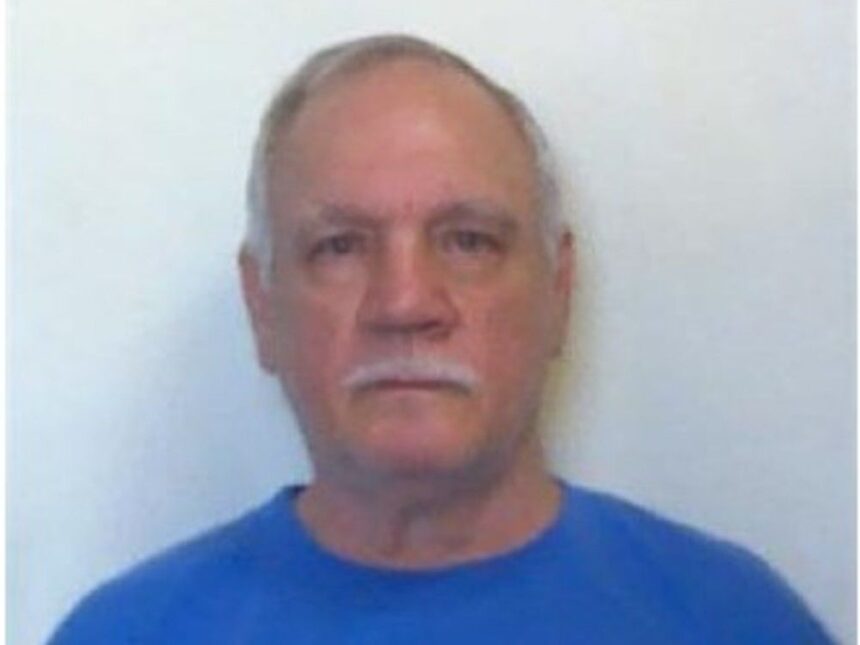

In a decision that has sent shockwaves through Halifax communities, Douglas Worth—convicted of the 1975 brutal murder of 12-year-old Susan Maynard—has been granted full parole despite fierce opposition from the victim’s family and local residents. The Parole Board of Canada determined last month that Worth, now in his late 60s, no longer poses a significant risk to public safety after spending nearly five decades behind bars.

The horrific crime that forever altered Halifax’s sense of security occurred when Worth, then 20 years old, lured young Susan into woodland near her home in Dartmouth. Court records reveal he sexually assaulted the child before strangling her and concealing her body in undergrowth. For three agonizing days, the community searched before making the devastating discovery.

“This release reopens wounds that never truly healed,” said Robert Maynard, Susan’s older brother, in an exclusive interview. “Our family has been serving a life sentence since 1975, and that sentence continues with no prospect of parole for us.”

Worth’s path to freedom has been methodically structured over the past decade. Initially granted day parole in 2015, he has resided in a halfway house under supervision while gradually receiving increased freedoms. Correctional Services Canada reports indicate he has participated in extensive rehabilitation programs and demonstrated “consistent remorse” for his actions.

The Parole Board’s decision states Worth has “developed significant insight into his criminal behavior” and notes his advanced age and declining health as factors diminishing recidivism risk. The Board further cited psychological assessments suggesting Worth’s risk of reoffending is “manageable within the community.”

However, victims’ rights advocates have expressed profound concern. Jennifer Matheson, director of the Nova Scotia Victims’ Services, questioned the decision: “When we release individuals who committed such heinous crimes against children, what message does that send to victims’ families who were promised that ‘life’ meant life?”

Worth’s release comes with stringent conditions, including geographic restrictions prohibiting him from entering certain areas of Halifax Regional Municipality, mandatory counseling sessions, and regular check-ins with parole officers. He is also forbidden from any contact with the victim’s family or unsupervised interactions with minors.

Criminal justice experts remain divided on the case. Professor Cameron Mitchell from Dalhousie University’s Department of Criminology notes, “The Canadian justice system is fundamentally based on the principle of rehabilitation, not just punishment. Statistics show that offenders in their sixties and seventies present dramatically reduced recidivism rates compared to younger populations.”

The community’s response has been swift and emotional. A memorial vigil for Susan Maynard drew hundreds last weekend, while an online petition demanding review of the parole decision has gathered over 15,000 signatures. Local political representatives have pledged to examine whether parole guidelines for particularly violent offenders require legislative review.

For Halifax residents who remember the summer of 1975, Worth’s release stirs complicated emotions about justice, punishment, and forgiveness. Many wonder whether any amount of rehabilitation can truly balance the scales when weighed against the life of a child and decades of family suffering.

As our society continues to grapple with these profound questions of justice and redemption, we must ask ourselves: What constitutes appropriate punishment for the most heinous crimes, and at what point—if ever—has a debt to society truly been paid?