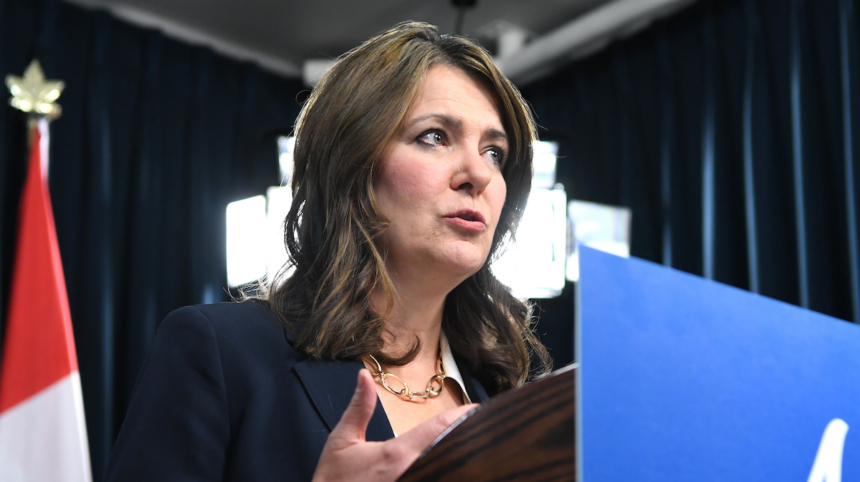

In a controversial move sending ripples through Alberta’s healthcare landscape, Premier Danielle Smith’s government announced last week that Albertans will soon need to pay for COVID-19 vaccines—a decision that appears driven more by ideological positioning than fiscal prudence.

The policy shift, scheduled to take effect April 1, ends universal free access to COVID-19 vaccines, limiting coverage to only vulnerable populations while requiring everyone else to pay approximately $30 per dose. Government officials have framed this as a “cost recovery” measure, but careful analysis reveals deeper motivations behind the change.

“This decision reflects our government’s commitment to fiscal responsibility and normalizing our approach to COVID-19,” stated Health Minister Adriana LaGrange when unveiling the policy. However, the financial justification quickly unravels under scrutiny. The federal government continues to supply vaccines at no cost to provinces, meaning Alberta’s “cost recovery” primarily refers to administration expenses—costs the province has routinely absorbed for other vaccines in its public health programs.

The timing of this announcement coincides with a period of heightened political posturing in Alberta, where pandemic measures have become sharply divisive. Smith, who rose to power partly by criticizing COVID-19 public health interventions, appears to be solidifying her political brand rather than implementing evidence-based health policy.

Public health experts have expressed alarm about potential consequences. Dr. Neeja Bakshi, an Edmonton internal medicine specialist, warned: “Charging for essential vaccines creates unnecessary barriers to preventive care. We know from decades of public health experience that even modest financial hurdles significantly reduce vaccination rates.”

The economic calculus also raises questions. Any short-term savings from user fees must be weighed against potential increases in healthcare costs from preventable COVID-19 hospitalizations. Each admission typically costs the healthcare system between $20,000 and $50,000—vastly exceeding administration expenses for vaccines.

This policy diverges from approaches in other Canadian provinces, where COVID-19 vaccines remain freely available to all residents. Alberta’s exceptional stance places it alongside only New Brunswick in restricting free vaccine access, creating what some critics call a “patchwork approach” to public health across the federation.

The Alberta Medical Association has called for reconsideration, emphasizing that vaccines represent one of the most cost-effective public health investments. “Prevention is invariably less expensive than treatment,” stated AMA President Dr. Paul Parks in a recent statement on COVID-19 policy.

Supporters of the change argue it represents a necessary transition to treating COVID-19 like other respiratory illnesses. However, this equivalency overlooks COVID-19’s significantly higher hospitalization rates and long-term health impacts compared to seasonal influenza.

Deeper analysis suggests this policy belongs to a broader pattern of decisions seemingly designed to signal political alignment rather than optimize public health outcomes. Smith’s government has previously challenged federal health measures and removed other pandemic protections, consistently framing public health as a matter of personal choice rather than collective responsibility.

As Alberta implements this controversial approach, residents face a fundamental question that extends beyond vaccine costs: In a modern healthcare system, should access to preventive care be determined by ability to pay, or do we recognize certain health interventions as public goods that benefit everyone when universally available?

The answer shapes not just our response to COVID-19, but the future of public health in Canada.