The snow-covered paths leading to Quebec’s Roxham Road once served as the primary irregular entry point for asylum seekers into Canada. Today, that flow has shifted dramatically to official ports of entry, with the Lacolle border crossing witnessing an unprecedented surge that threatens to overwhelm provincial resources and reignite national debates on immigration policy.

Recent data from the Canada Border Services Agency reveals that asylum claims at Quebec’s ports of entry have skyrocketed by 353% in just two years. In the first quarter of 2024 alone, over 15,000 asylum seekers entered through Quebec’s official border crossings—numbers that provincial officials describe as “simply unsustainable” under current support frameworks.

“We’re seeing numbers that exceed our operational capacity,” explained François Dornier, director of Quebec’s refugee settlement program. “The federal government closed Roxham Road last year, but the pressure has simply transferred to official entry points, particularly Lacolle, without addressing the underlying issues.”

The surge coincides with the implementation of the revised Safe Third Country Agreement between Canada and the United States in March 2023, which closed the loophole that had made Roxham Road a preferred crossing point. While successful in reducing irregular crossings, the policy appears to have merely redirected asylum seekers to official ports of entry, where they can still legally make claims.

Quebec Premier François Legault has intensified calls for federal intervention, requesting additional resources and a more equitable distribution of asylum seekers across Canadian provinces. “Quebec welcomes immigrants with open arms, but we currently host a disproportionate percentage of Canada’s asylum seekers while managing just 22% of the country’s population,” Legault stated during a press conference earlier this week.

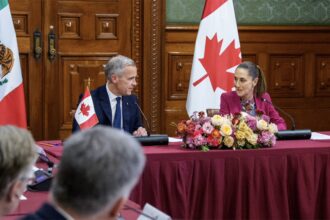

Federal Immigration Minister Marc Miller acknowledged the challenges during a visit to Montreal, announcing $150 million in emergency funding to help Quebec manage the immediate crisis. “We recognize the extraordinary pressure facing Quebec’s social services and housing systems,” Miller said. “This funding represents a first step, but longer-term solutions require cooperation across all levels of government.”

The impact extends beyond government agencies. Community organizations report significant strain on housing, healthcare, and education services. Mohammed Alsaleh, director of the New Arrivals Support Network in Montreal, described the situation as reaching “critical mass” in certain neighborhoods.

“Many newcomers are sleeping in temporary shelters for months because affordable housing is virtually non-existent,” Alsaleh explained. “Schools are struggling to integrate children who require specialized language support, and healthcare clinics are operating beyond capacity.”

The crisis has reignited debate about Canada’s immigration policies at a time when public sentiment appears increasingly divided. A recent Angus Reid survey indicates that 57% of Canadians believe the country should accept fewer immigrants overall, while 68% express concern about the government’s ability to effectively manage asylum claims.

Immigration experts point to global factors driving the increase. Dr. Audrey Macklin, professor of immigration law at the University of Toronto, notes that “climate disasters, political instability, and economic collapse in various regions have created unprecedented migration pressures worldwide. Canada isn’t unique in facing these challenges, but our geography has historically insulated us from the immediate impacts experienced by countries with land borders to conflict zones.”

The current situation presents a significant test for Prime Minister Justin Trudeau’s government, which has consistently positioned Canada as a welcoming destination for refugees and immigrants. Critics from both sides of the political spectrum argue that the current approach lacks coherence, with Conservative opposition leaders calling for stricter border controls while progressive voices advocate for expanded support systems.

Meanwhile, at the Lacolle crossing, border services officers process hundreds of asylum claims daily in facilities designed for a fraction of that volume. One officer, speaking on condition of anonymity, described working conditions as “completely untenable” with staff facing burnout and mounting paperwork backlogs.

As winter approaches, bringing harsher conditions that typically reduce crossing numbers, both provincial and federal authorities are racing to implement more sustainable solutions. The question remains: can Canada develop an asylum system that balances humanitarian obligations with practical resource constraints, or will political divisions prevent the emergence of a cohesive national strategy on this increasingly contentious issue?