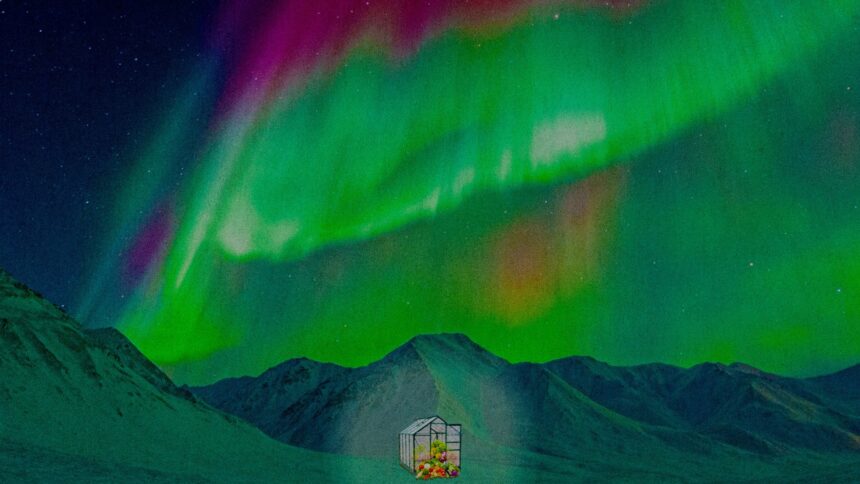

In the harsh climate of Labrador, where winter temperatures regularly plummet below -30°C and the growing season barely stretches beyond 100 days, a quiet agricultural revolution is taking root. Deep beneath the frost-hardened soil lies an unexpected ally in the fight for food security: geothermal energy, which is now powering year-round greenhouse operations across the region.

“What we’re witnessing is nothing short of transformative,” explains Dr. Sarah Winters, agricultural scientist at Memorial University’s Labrador Institute. “Communities that once relied almost exclusively on imported produce can now access fresh vegetables throughout the year, even during the darkest winter months.”

The pioneering initiative began three years ago when the provincial government partnered with Indigenous communities to drill the first geothermal wells near Happy Valley-Goose Bay. By tapping into the steady 7-10°C temperatures found deep underground, these systems provide reliable heating for greenhouse structures without the prohibitive energy costs that previously made year-round growing economically unfeasible.

For residents like Elizabeth Mishkin, a mother of three in Nain, the impact has been immediate. “Before the community greenhouse opened, a head of lettuce could cost $8 in winter, if you could find it at all,” she tells CO24 News. “Now we’re growing everything from tomatoes to herbs, and my children actually know what fresh vegetables taste like in February.”

The statistics support these anecdotal successes. According to data from the CO24 Business economic analysis team, communities with operational geothermal greenhouses have seen average household food costs decrease by 22% since implementation. Nutritional intake metrics show increased consumption of fresh produce by 37% across all age groups.

What makes these projects particularly noteworthy is their integration of traditional Indigenous knowledge with modern technology. In Makkovik, the greenhouse operation incorporates traditional Inuit planting calendars and cultivation techniques alongside computerized climate control systems powered by geothermal energy.

“This isn’t just about growing vegetables; it’s about food sovereignty,” states Thomas Palliser, food security coordinator for the Nunatsiavut Government. “For generations, our communities have been at the mercy of southern supply chains and weather-dependent deliveries. Geothermal technology gives us control over our food systems again.”

The environmental benefits extend beyond food security. The Canada News environmental assessment division reports that each operational greenhouse reduces carbon emissions by approximately 85 tonnes annually compared to the transportation footprint of importing equivalent produce from southern Canada.

The success has prompted expansion plans throughout Labrador and into other northern regions. The federal government recently announced $47 million in additional funding to establish similar operations in twenty more communities across Canada’s North over the next five years.

As other circumpolar nations take notice, delegations from Alaska, Greenland, and northern Scandinavia have visited Labrador’s greenhouses in recent months. “What we’re seeing here could revolutionize food production across the Arctic,” notes Finnish agricultural attaché Matti Järvinen during his visit to Hopedale’s facility.

Critics point to the substantial upfront investment—each geothermal system costs approximately $2.3 million to install—but proponents counter with compelling long-term economics. “The systems pay for themselves within seven years through reduced food costs and create permanent local employment,” explains economist Dr. Alan Thompson of the Northern Development Institute.

As climate change continues to disrupt traditional hunting and gathering practices in the North, these greenhouse initiatives represent a crucial adaptation strategy. But they also raise a profound question: in our rapidly changing world, could ancient heat from deep within the Earth become the key to northern food security, and will we act quickly enough to harness it where it’s needed most?