In the rugged landscapes of northern Ontario, a quiet revolution is taking place. The Bilijk First Nation has transformed their relationship with food from one of dependency to self-determination, creating a model of Indigenous food sovereignty that communities across Canada are beginning to emulate. As climate change and food security concerns intensify globally, their traditional knowledge systems offer sustainable solutions with far-reaching implications.

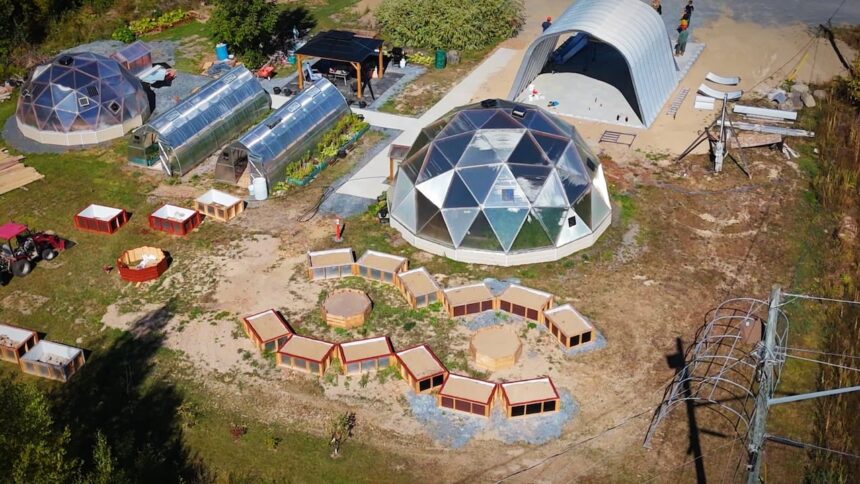

“Food isn’t just sustenance for us—it’s our medicine, our connection to ancestors, our sovereignty,” explains Elder Martha Whiteduck of the Bilijk First Nation. “When we reclaim our food systems, we reclaim our future.” The community’s journey began five years ago with the establishment of a 30-acre agricultural initiative that now produces traditional crops including the “Three Sisters”—corn, beans, and squash—alongside medicinal plants that had nearly disappeared from the region.

The significance extends beyond mere food production. According to Indigenous food sovereignty expert Dr. Thomas Bearhead, these initiatives directly address the systemic food insecurity plaguing many First Nations communities. “What we’re witnessing at Bilijk is the practical application of intergenerational knowledge that predates colonial boundaries. Their success challenges the narrative that remote communities cannot achieve food self-sufficiency,” Bearhead told CO24 News.

The economic impact has been substantial. The Bilijk initiative now employs 27 community members and has launched a seed-saving collective that preserves heritage varieties specifically adapted to northern growing conditions. Their harvest-sharing program distributes traditional foods to elders and families while creating economic opportunities through value-added products sold across Canada.

Federal attention has followed these grassroots successes. Indigenous Services Canada recently announced a $24.5 million investment in similar initiatives nationwide, acknowledging what Indigenous communities have long maintained—that food sovereignty is inseparable from cultural revitalization and economic resilience.

“We’re seeing a paradigm shift,” notes Climate Policy Analyst Samantha Greeneyes. “These aren’t just agricultural projects—they’re comprehensive responses to colonial disruptions that severed Indigenous peoples from traditional food systems.” The Bilijk model incorporates wild food harvesting, intergenerational knowledge transfer, and climate adaptation strategies developed over thousands of years.

The revival of traditional food systems also addresses pressing health concerns. Community health director James Running Water reports a 22% decrease in diabetes indicators among participants in the program. “When we return to our traditional diets, our bodies respond. The health benefits are measurable and significant,” he explains.

Perhaps most compelling is the youth engagement component. The Bilijk initiative includes a dedicated learning program where elders teach young people traditional harvesting, preparation, and preservation techniques. Seventeen-year-old participant Skylar Thundercloud describes the experience as transformative: “I’m learning things my grandparents knew but that almost disappeared. Now I understand food isn’t just what you eat—it’s who you are.”

As climate uncertainty threatens conventional agriculture, the Bilijk approach demonstrates remarkable resilience. Their integrated growing systems withstood both drought and flooding events that devastated nearby conventional farms. This adaptability has attracted interest from environmental scientists studying climate-resilient food systems for the future of Canadian agriculture.

The question now facing policymakers and communities alike is whether this Indigenous-led model can scale nationally while maintaining its cultural integrity. Can Canada embrace food sovereignty principles that challenge existing agricultural paradigms and power structures, or will these initiatives remain isolated successes in a system still shaped by colonial approaches to land and food?