The silent collapse of insect populations across protected nature reserves has reached crisis levels, triggering profound concern among ecologists worldwide. Recent comprehensive studies reveal that even in supposedly pristine conservation areas—lands specifically designated to preserve biodiversity—insect numbers have plummeted by an estimated 45-60% over the past three decades, fundamentally altering ecosystem dynamics in ways that may prove irreversible.

“What we’re witnessing isn’t just a decline—it’s a systematic emptying of entire ecological communities,” explains Dr. Eleanor Saunders, conservation biologist at the University of British Columbia. “These nature reserves were meant to be our ecological insurance policies, but the data suggests they’re failing to protect even the most fundamental links in the food web.”

The findings are particularly troubling because nature reserves represent our best-case scenario for wildlife protection. Designated areas in southern Ontario’s Carolinian forest region, for instance, have recorded 57% fewer flying insects since 1990, despite being protected from direct development and agricultural activity. Similar patterns have emerged across reserves throughout Canada and globally.

This dramatic loss carries cascading effects through entire ecosystems. Birds that rely on insects have declined by nearly 30% in these same reserves, while plant pollination rates have fallen by up to 40% in some protected areas. According to research published in the journal Ecological Integrity, these changes represent nothing short of a “fundamental restructuring of food webs.”

Climate change bears significant responsibility, with warming temperatures disrupting insect life cycles and breeding patterns. However, recent analysis points to more complex factors. Chemical contaminants, particularly neonicotinoid pesticides, have been detected within nature reserve boundaries despite no direct application—evidence of their alarming environmental persistence and mobility.

“These chemicals don’t respect the invisible boundaries we’ve drawn around protected areas,” notes Dr. James Chen of Environment Canada’s Wildlife Research Division. “They travel through watersheds, on wind currents, and can remain active in ecosystems for years. What happens on agricultural land 50 kilometers away ultimately affects our most protected spaces.”

Light pollution represents another underappreciated threat. A comprehensive study of 24 nature reserves across North America found that artificial light at night has increased by 270% since 1992, disrupting nocturnal insect navigation, breeding, and feeding behaviors. Even reserves far from urban centers show measurable increases in ambient light.

The crisis extends beyond environmental concerns into economic territory, with ecosystem services provided by insects—including pollination, decomposition, and natural pest control—valued at approximately $57 billion annually to the Canadian economy. Agricultural yields in regions surrounding depleted reserves have already shown measurable declines, particularly for crops dependent on wild pollinators.

Conservation strategies are being urgently reconsidered. Traditional approaches focused on simply setting aside land have proven insufficient against these pervasive, borderless threats. New frameworks being developed by Parks Canada and provincial conservation authorities now incorporate buffer zone management, watershed-scale planning, and regional coordination of agricultural practices.

“We need to fundamentally reimagine what protection means,” argues Dr. Saunders. “A fence and a ‘keep out’ sign clearly isn’t enough anymore. Conservation in the 21st century requires managing entire landscapes as interconnected systems.”

Canadian politicians have been slow to respond, despite mounting scientific evidence. While the European Union has implemented aggressive restrictions on particularly harmful pesticides and light pollution controls, Canada’s regulatory approach remains fragmented across provincial jurisdictions with inconsistent standards.

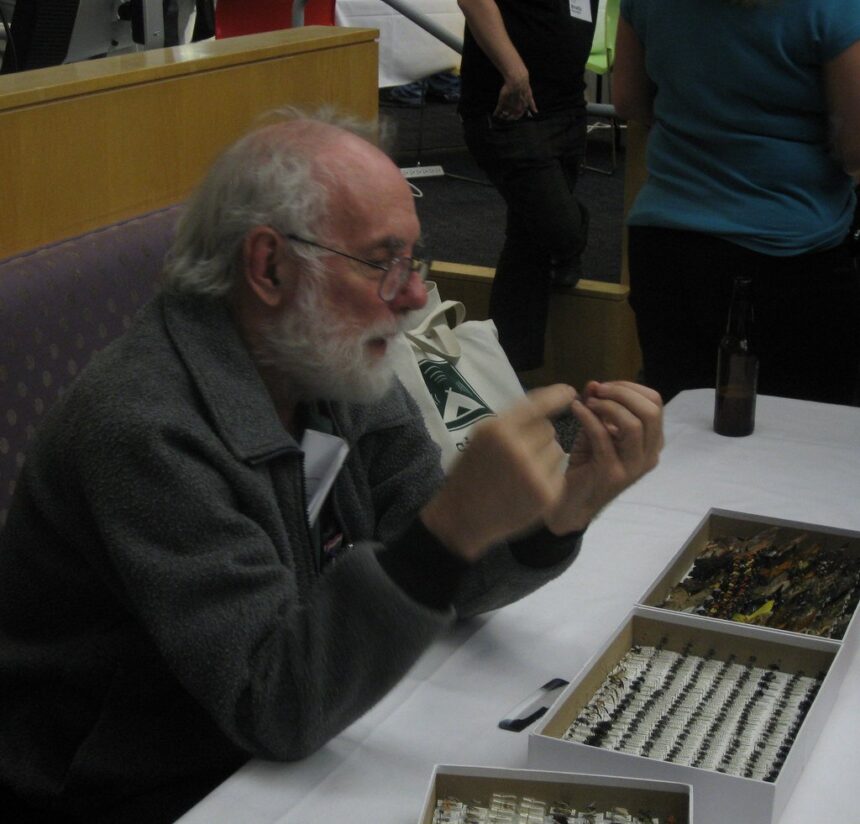

Citizen science initiatives offer one promising development. The National Reserve Monitoring Network has recruited over 7,000 volunteers to conduct standardized insect surveys across 130 nature reserves nationwide, creating the most comprehensive dataset of its kind and bringing much-needed public attention to the crisis.

Hope may lie in the remarkable resilience some insect species have demonstrated when given the chance. Pilot recovery projects in select Ontario reserves have shown that implementing stricter buffer zones, targeted habitat restoration, and coordinated regional pesticide reductions can yield insect population increases of 15-30% within just five years.

As we confront this profound ecological shift, the question becomes increasingly urgent: are we prepared to rethink our entire approach to conservation before these silent reserves become permanently emptied of the very biodiversity they were designed to protect?